The cemetery was pitch black. Not just pitch black, but the sort of darkness you can find only in the country, at the top of a hill, beside an old chapel, in the middle of the night … during a 100-mile trail race.

My younger brothers, my mom and I were waiting for my dad to emerge from that darkness. Then, it would be a flurry of activity. There were no cell phones then on which he could call and tell us to have at-the-ready his new socks, or dry shoes, a flashlight with fresh batteries, Power Bars, or a baked potato or burrito. So we’d pull out all we could think of, my mom would guess at what he may want, and we’d holler as soon as we saw his flashlight, “What do you need?”

This, as the saying goes, wasn’t our first rodeo.

My dad had run the first Mohican 100-Mile Trail Race in June 1990, when it was uncharacteristically chilly and rained most of the race. There were multiple river crossings, and at one point, the runners even splashed through the river and ran up the hill right by our campsite, in the “Deep Woods” section of the family-owned campground that hosted the race then and that would quickly become our second home.

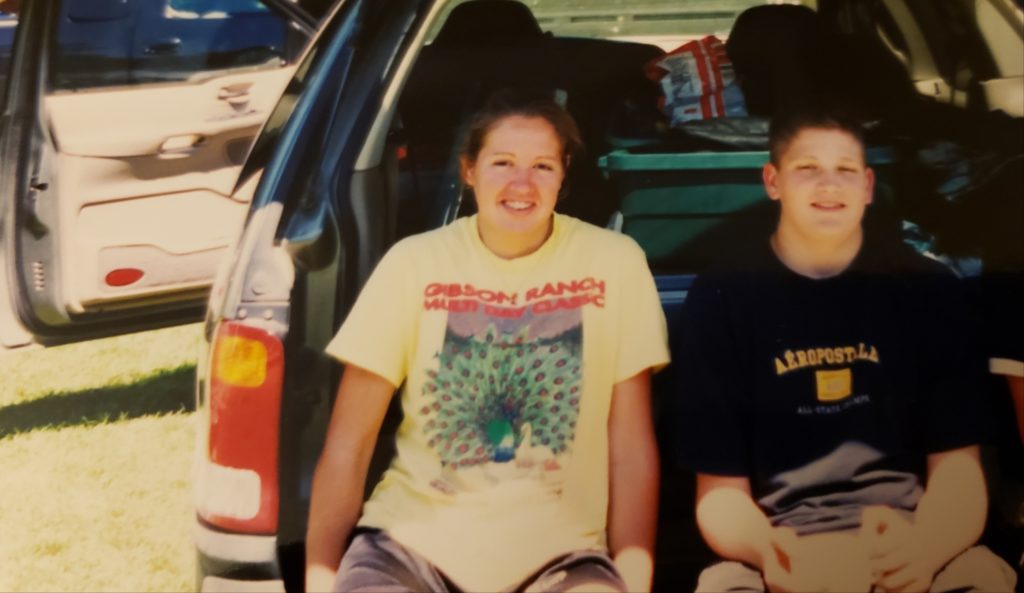

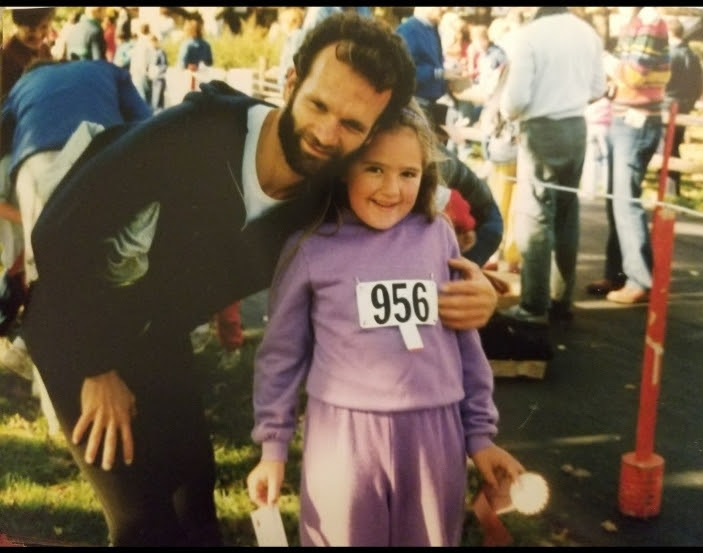

My dad ran the first 13 Mohicans in a row. But at that first race, I was 10 and my brothers were 7 and 2. My mom took three elementary-school kids traipsing around the backcountry of Ohio. Now that I’m a mom, I see what an ordeal that really was. When I ran a trail 50K, this past December, my husband and I asked my mom to watch our boys, who are 9 and 13, mainly to make it easier and less stressful on all of us. Yet my mom packed for a family of five to camp for a whole weekend, and chase my dad around in chilly, rainy weather – with a 2-year-old, no less.

Every year after that first one, the Mohican 100s were hot. Very hot, and humid. Temperatures in the mid- to high-90s. Choking humidity. Mosquitos. So many mosquitos, in that sticky heat that dripped from the runners’ caps and left even the crews feeling lethargic.

While waiting at aid stations and crew points, my brothers and I would play first-bounce-fly or tag, or scale the fire tower to look out over the forest, then, when the heat truly set in, we would read, color and snack. (There was a lot of snacking.)

The woods were cooler, with the shade, but they also trapped the heat. Breezes didn’t flow as easily. My dad would emerge from the woods with legs criss-crossed with red, angry briar scratches, and I would go home to Columbus, which seemed so much more claustrophobic and penned in than when I’d left just days before, covered in itchy bug bites that I would scratch relentlessly throughout the night.

But I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

We were used to the shocked comments people would utter when they heard my dad ran 50-100-, even 200-mile trail races, or had run across Ohio. Now, they’ve become well-known jokes, even memes, but then, when ultra running and trail running were in their infancy, people were more unsure what to make of it:

“I get tired just driving that far.”

“Run? 100 miles? In the woods?”

“Do you sleep? Eat? Go to the bathroom? When? Where?”

“How does one prepare for something like that?”

“Well! Better you than me!”

We didn’t follow my dad just to ultras, but also to marathons and other road races. At the Pittsburgh Marathon one year (we think it was 1989), we waited and waited (in pouring rain) for my dad. He should have come through that mile long before, but we had no idea where he was. We had no phones, no way to contact him, and we didn’t know what could have happened, leaving our imaginations to devise all sorts of scenarios.

We finally saw our family friend, Del, and found out my dad was in the medical tent. He’d recently allowed an exercise physiology class at The Ohio State University, his alma mater, to run tests on his leg for research purposes; they’d taken biopsies of his calf, but something had gone wrong, and he’d developed a fist-sized hematoma in his muscle.

There were less scary, more joyous moments. My dad won a Muncie, Indiana race and with it, the $500 prize money. A picture that ran in the Indiana Runner publication shows my dad holding up both hands, fingers splayed and mouthing, “500.” That was a lot of money for our struggling family; we lived off my dad’s $20,000 salary as a unit clerk at OSU’s Dodd Hall and the $2-an-hour income my mom took in babysitting children in our home so she could be with us.

Nearly all of our childhood trips were to races. Even now, that would be uncommon. Kids now go to Disney World, Florida, the Outer Banks. I suppose the wealthy kids did that in the 80s and 90s, too, actually, yet I never pined for such trips.

In crewing for my dad at all these races, I had an up-close view of determination and humanity at its finest and its weakest moments. Running often is used as a metaphor for life, and that’s because it’s true. I saw my dad near tears, in pain, feeling like he couldn’t go another step – but then going miles more.

I saw my mom remain calm, even when he yelled, and get him what he needed, and tell him he could keep going, all while herding three kids.

I saw people stumbling through the dark, swatting clouds of bugs, howling in pain as cramps seized their legs, collapsing into lawn chairs at aid stations. It would have been easy – so much easier – to stay there, but they got up, wiped sweat and dirt from their faces, inhaled a cheeseburger, and disappeared back into the firefly-lit night.

When I was in 7th grade, my dad, along with four other runners, did the Run Across Ohio for the Homeless. It started the first Monday of December in Cincinnati and finished that Friday in Cleveland. My mom, brothers and I rode in an RV provided by the run, complete with a car phone (the first I’d ever seen). The runners ran a harrowing 249 miles on the shoulder of Route 3, an often-busy highway that crosses the state. The runners had plenty of near-misses with cars. In Columbus, they ran up North High Street, right past our elementary school, and my brother’s class came out on the front steps of the school with signs and cheers.

Two years later, when I was in 9th grade, my biology teacher, Mr. Koch, would point me out in class on the day after that year’s Columbus Marathon, and congratulate my dad for running a 3:15. It wasn’t his fastest, and most of the kids in my class, too busy dealing with gang life, or teen pregnancies, or how their single moms would pay rent while their dads were in jail (I’m not kidding), probably had no idea a marathon had occurred the day before, but I was proud that my teacher had found my dad’s name in the list of results.

When I was in college, my dad started a 200-mile race that did the Mohican course twice. He served as race director and took part, and once again, our family was his crew. As I had classes to attend, I would drive down when I could and meet the rest of my family along the course. One night, my mom and brothers were in our van and I was in my Jeep; we were parked at the Pleasant Valley dam, waiting for my dad. It was the middle of the night and I was awakened by a park ranger rapping on the plastic, tent-like window of my Wrangler.

“What are you doing?” he said.

“I WAS sleeping,” I answered in what I now see as a sign of my lifelong shyness evaporating along with my extra weight, and my true snarkiness beginning to emerge. As my dad didn’t actually have all the proper permits and was doing the 200 miles more as a fun run, I couldn’t say exactly why I was parked there.

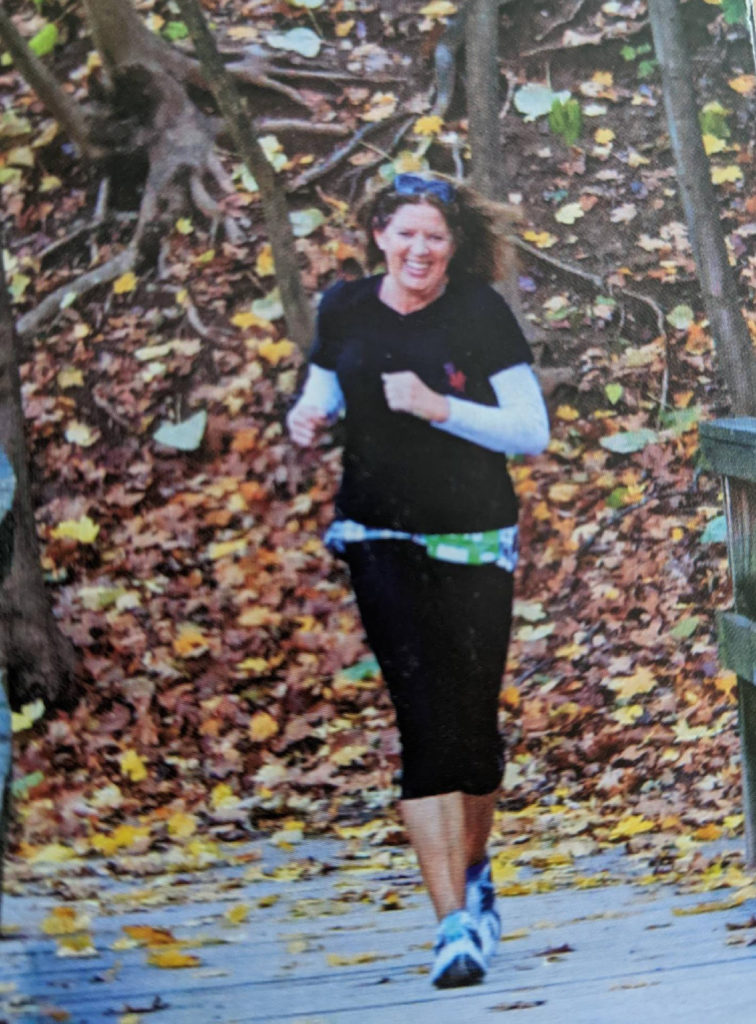

Crews often shoulder a lot of the responsibility for an ultrarunner’s success. Yet my mom had been a runner in her own right. Once we kids came along, however, and my dad was running 50-mile training runs on weekends, someone had to watch us and keep the house going, and that job fell to her – until my dad left in 2005 and she took up running again, competing in halves and marathons. Every year on her birthday, she walks/runs her age. It used to be in a single day, then she started suffering from hip and leg issues, and it now is during the week leading up to it.

I often think about how my mom had to give up something she liked and was good at (she apparently was faster than my dad when they met) to raise kids and do everything at home. Now, I’m the one going out for long trail runs on Saturday mornings while my husband stays home with the kids. The vast majority of the child-rearing and household chores still falls on me (I’ve sometimes come home and met a mess that made me want to turn around and run right back out), and I usually run early in the mornings before anyone is up, or leave in the pre-dawn hours for Saturday trail runs an hour away so I’m not gone the whole day. But my generation (or some of us – many of my friends still speak of asking their husband’s permission to do things, an idea I find infuriating) has been told we can do it all. (It’s not true – we can’t do it all, or maybe we can, at a huge impact to our mental health … but, if we want to run, at least, we usually find a way.)

I didn’t run cross country or track as a kid, although I did play basketball. For most of my childhood and teen years, I was an overweight, shy kid. I played outside all the time, biking, running, rollerblading; I played basketball on my school teams and outside after school, but it didn’t make a difference to my weight. At Mohican, I’d “pace” my dad, running a short section near the end of the 100-mile race with him. Accomplishing such a feat myself, at some point, seemed a given, in that hazy adulthood that seemed so far off (although I also remember telling my mom with certainty that I was going to marry a runner), but attempts to lose weight failed, and bouts of running with my dad through Columbus’s ravines in the summer heat didn’t develop into daily habits.

That finally changed the December of my freshman year of college, when I somehow found the motivation to eat way fewer calories than I should have been and work out like a fiend, thereby dropping 68 pounds (but developing lingering body issues that remain to this day). I began running most days, mainly as a way to lose and keep off weight, but also because it was something that was in my DNA. I’d run the country roads around the farmhouse we rented at the time, often alone, sometimes with my dad. On summer evenings, my dad and I would sometimes run through the forests and the backroads of Mohican, stopping on the way home at a gas station near our house for bottled SoBe pina coladas – my introduction to a post-run reward that now comes in the form of coffee.

When I was 20, I entered and ran a 24-hour race, the same one my dad was doing and had done for years (even winning one year with 139.4 miles).

With no real training, other than the few miles most days I was running for fitness, I ran 56.4 miles around the 1.1-mile loop through a picturesque city park. I had given no real thought to fueling or strategy; I would eat what my mom brought, which was what my dad ate. My plan was to just keep going. I ran when I could, walked when I couldn’t, and napped for a couple hours near dawn in our tent, set up in a grove of trees amongst others near the canopy that marked the end of one loop and start of another.

There were no chips attached to bibs or shoes then; instead, we wore slips of paper bearing unique barcodes, attached to our clothes with safety pins. As we went through the canopy each loop, we tore off a slip and dropped it in a basket on a table for the race volunteers to scan.

When the gun went off, signaling noon on Sunday and the end of the 24 hours, I was at one of the farthest points from the finish line, across the lake, in a treed area bordering the surrounding neighborhood; I dropped to the ground right where I was, and my mom snapped a picture of me lying sprawled across the pavement, half-exhausted and half-joking.

I often think that I should do a 24-hour race now, and I plan to, but it would be different. I’d train, and I’d overthink what clothing and fuel to bring, packing too much. And then I’d start and I’d maybe run twice as far as I did when I was 20, or maybe my legs would seize up, or my stomach couldn’t handle it, and I’d be lucky to make it to 50 miles.

Race day is its own kind of beast.

Maybe just doing it – running it on a whim because it’s what you’ve grown up with and it’s what you know, regardless of training or fueling or plans … maybe that’s the way to do it.

And it helps, I suppose, if you have a support network. They aren’t hard to find now. Social media has made it difficult to sometimes do anything that feels new, that feels as if no one has done it before. And that’s hard for people like me, who’ve never wanted to follow the herd, but have found comfort instead in going against the grain.

My family had its own group of weird ultrarunners when I was growing up. These were the people we’d see at trail races throughout the year. They are the names I’ve known since I was 7, 10 … names that now are well-known within running, or at least in the Ohio running community, but who were once part of this strange little circle of endurance athletes doing things that most found impossible.

It sounds bad, I know it does, but I don’t love that trail running and ultra running have grown in popularity. What sounds even worse is that I often get annoyed by those new trail runners who have a sort-of evangelical take on it: they are new converts, they have seen the light, the glorious light, and because of that, they are instant experts.

The pandemic hasn’t been great for those of us who like to go out in the woods to find quiet and solitude. When lockdowns occurred in 2020, the outdoors suddenly was flooded with people more used to spending their time in malls or movie theaters. My middle brother, mom and I have discussed our annoyance at our once-private places becoming inundated with people.

I suppose, as with anything, we all have to carve out our own way to continue to enjoy the things that are inherently a part of us, even when those things change.

While I often can’t stand to run alone for shorter road runs in my neighborhood, and do most of these in the pre-sunrise darkness with friends, I relish a long, solo trail run. I put on a podcast and go – for eight, 10, 12, 14 miles through trails made slippery by fallen leaves that hide jagged rocks. I scale hills and come around turns, not knowing exactly what is in the next quarter mile, as it changes by the season or the day: a fallen tree that wasn’t there a month ago, a fresh snowfall, a mud pit that sucks at shoes.

Trail and ultra running may have grown in popularity, but they still, at their core, are what they were when I was a kid, waiting in the muggy dark for my dad to emerge from the woods: they force you to stretch beyond what you thought was possible, to keep going when you think you can’t. To go further than you once could. I bet that shy, overweight teenager who got winded running a mile, watching her dad cross the 100-mile finish line, would be pretty proud of how far she’s come.

One Response

I cannot thank you enough for your article and how much I enjoyed reading it.

Your experiences brought back many memories for me of Mohican. I started marking trails in the mid 1990’s when we hung plastic ribbons from trees to mark the trails, then take the ribbons down after the race. Trail marking was quite an ordeal in those years. I worked the aid station at the Fire Tower, and several others as well. I remember the heat and some of the rain years, and at the time it didn’t seem like much fun, but now I look back on those years fondly with a smile. Mohican week was a big event for me.

And I do remember seeing your mom, you, and your brothers crewing for your dad at some of the aid stations. Your dad would always talk about you during some of our training runs at Mohican as conversation about family and food usually come up during the hours of running through the woods. And your dad did like to run for hours.

In February 2002, your dad and I went to run David Horton’s Holiday Lake 50K. He was a talker and great company during the trip to Virginia and back. Based on my name, as soon as Horton saw my entry at the registration, I was ZZTop(for the whole weekend). I’ve met many interesting people in doing ultras, your dad is one of them, and I’m glad that our paths crossed in friendship.

I’m very happy you wrote this article.