*Updated from the 2017 article “When the Forest is on Fire”

Feature Photo: Jeff Fisher

Where there’s fire, there’s smoke. Where there is a big fire, there is smoke for a long time. As I write this, there are several million acres of wildfire in Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho and Montana still raging. Australia saw 46 million acres burn this year. Wildfires produce smoke particle pollution, which, when present in high enough concentration, will cause respiratory symptoms in most people. Wildfires are a global crisis.

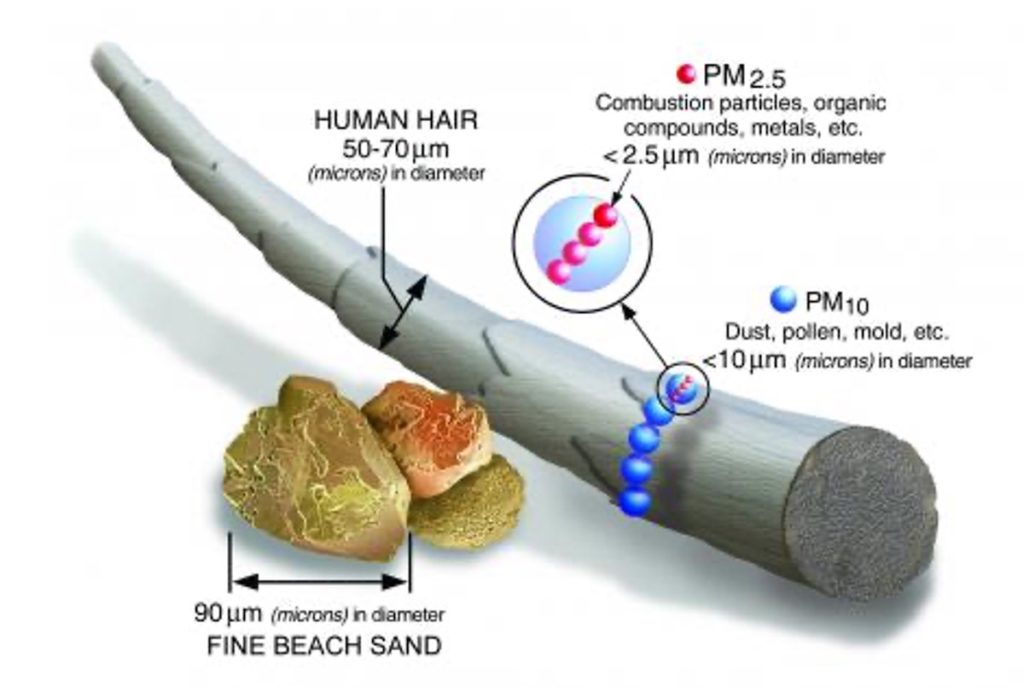

The air quality index (AQI) across the American West has been between 200-500+PM2.5 for weeks. The upper safe limit for healthy individuals is AQI 150PM2.5, anyone with sensitivity or respiratory disease will be affected even at AQI 75PM2.5.

Photo Credited to EPA.GOV

Unfortunately, certain areas like Australia, Northern California, Western Oregon and the Great Plains are predicted to have ongoing issues with wildfires for the foreseeable future. We run in the forests, and those forests are going to be predictably on fire each year. We’re seeing not only the forested areas being affected, but the nearby urban areas as well. Wildfire season is its own distinct season, and one that all runners need to factor into the rhythm of the year. Climate change recognition is important now more than ever.

We are still weeks out from 100% containment, and people are beginning to wonder, “Is it safe to run yet? Is it safe to even be outside?” If your area is at 150 AQI or higher, the answer is no. This is not a safe level for exerting outdoors. If the AQI is 150 or less, proceed with caution. You can still sustain lasting damage from smoke exposure.

There are two pathways of injury that occur when smoke particles come in contact with our respiratory system. Initially, the particles cause inflammation at the site (the lungs), and subsequently those cells sustain oxidative damage (cell death and/or mutation). Inflammation of the lungs is what causes asthmatic-type symptoms: wheezing, constriction, and coughing. Oxidative stress, when repeated, leads to lasting tissue damage and eventually lung scarring and disease.

Additionally, processing the toxicity generated from wildfire smoke causes our detoxification pathways to work overtime. We get rid of toxins through peeing, pooping, sweating, and finally exhaling. The liver and kidneys must keep up with their normal daily tasks AND manage a sudden influx of particles. In AQI 150 and higher, people are more likely to report symptoms of nausea, headache, fatigue, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness. It’s a lot like having a bad hangover, because, like overindulging in alcohol, our body is at a distinct disadvantage with slower processing.

So, what’s a trail user to do with that information? A one-time exposure to polluted air may have you coughing for a few days, but accumulated exposure over time is a different beast altogether. Lungs that function well are pretty helpful for any outdoor activity. The first thing to do is to assess your relative risk. Have you ever had asthma? Do you feel especially sensitive to environmental changes and air quality? If so, you’ll want to bookmark your local air quality monitoring station to stay updated.

High-risk groups include:

- People with cardiovascular disease

- People with lung disease, such as asthma and COPD

- Children and teenagers

- Older adults

- New or expectant moms that want to take extra measures to protect their babies.

If you find that you’re in a high-risk category AND the air quality is rated as anything beyond “GOOD”, these are the lung-friendly choices to make:

- Choose a less-strenuous activity

- Shorten your outdoor activities or exercise indoors to 20-30 minutes (wear a mask)

- Reschedule activities: In some areas, the air quality is better first thing in the morning, but check the air quality monitor before going out.

- Spend less time near busy roads

- Sweat it out in a sauna or hot bath instead

They say an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. That’s a true story. In the case of wildfire smoke exposure, the window of prevention is small, but completely worth taking advantage of. When we think again of the two pathways of injury, inflammation and oxidative damage, we can start to understand which preventive measures we can take. My favorite way to combat inflammation is through diet:

INCLUDE plenty of these anti-inflammatory foods in your diet:

- Tomatoes

- Olive oil

- Green leafy vegetables like spinach, chard, kale

- Nuts and seeds

- Fruits such as strawberries, blueberries, cherries and oranges

- Fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, tuna and sardines

EXCLUDE the following, as they are the MOST inflammatory:

- refined carbohydrates, such as white bread, pasta, pastries

- French fries and other fried foods

- soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages

- red meat (burgers, steaks) and processed meat (hot dogs, sausage)

- margarine, shortening, and lard

The lungs love sulphur-containing foods and supplements to maintain a healthy lining and to make glutathione and taurine. Glutathione is necessary for our liver detoxification pathways to function properly, another component of post-exposure care. Go liver! Go lungs!

INCLUDE sulphur-containing foods to lower oxidative stress:

- Arugula

- Coconut milk, juice, oil

- Cruciferous veggies, including: bok choy, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, horseradish, kale, kohlrabi, mustard leaves, radish, turnips, watercress

- Dairy (except butter)

- Eggs

- Garlic, chives

- Legumes and dried beans

- Meat and fish

- Nuts

- Onions, leeks, shallots

IMPROVE your routes of detoxifcation and elimination:

- Drink half your body weight in ounces of either water or herbal tea. If you consume caffeine (say 16oz of coffee), be sure to add in half that amount again of water (another 8oz), since caffeine is a diuretic (makes you pee more).

- Fiber, roughage, and foods that move digestion along (such as beets, leafy greens, corn, seeds, brassicas). If you’re prone to slow bowel transit or constipation, be proactive and take the medicines and foods you know you need to keep things moving along.

- A few drops of bitters in warm water first thing in the morning will help stimulate digestion as well

If you make the decision to adventure outside before the air quality in your area has been designated as “GOOD” again, invest in proper particle-filtration masks. A buff or bandana might relieve some dryness, but will not filter out small particles generated from wildfire smoke and ash. Exercise in AQI greater than 150 requires use of an N95 or N100 mask. Your mask should have two straps that go around your head and fit well. If you run in areas known for wildfire events, you’ll want one in your hydration pack in the event that you get caught in an area with smoke. This happened to me exactly once, and a wet bandana was not as helpful as I would have liked.

If you have known smoke exposure and are experiencing increased respiratory symptoms either with or without running, it’s important to talk to your doctor immediately about your treatment options.

Medical Disclaimer. The information on this site is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. All content, including text, graphics, images and information, contained on or available through this web site is for general information purposes only.

SOURCES:

Respirology. 2009 Jan;14(1):27-38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01447.x. Impact of oxidative stress on lung diseases. Park HS1, Kim SR, Lee YC.

Clim Change. 2016 Oct;138(3):655-666. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1762-6. Epub 2016 Jul 30. Particulate Air Pollution from Wildfires in the Western US under Climate Change. Liu JC1, Mickley LJ2, Sulprizio MP2, Dominici F3, Yue X2, Ebisu K1, Anderson GB4, Khan RFA1, Bravo MA5, Bell ML1.

Environ Res. 2015 Jan;136:120-32. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.015. Epub 2014 Nov 20. A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke. Liu JC1, Pereira G2, Uhl SA3, Bravo MA4, Bell ML5.

Geohealth. 2017 Mar;1(3):122-136. doi: 10.1002/2017GH000073. Epub 2017 Mar 31. Comparison of wildfire smoke estimation methods and associations with cardiopulmonary-related hospital admissions. Gan RW1, Ford B2, Lassman W2, Pfister G3, Vaidyanathan A4, Fischer E2, Volckens J5, Pierce JR2, Magzamen S1.

Non-Accidental Health Impacts of Wildfire Smoke. Hassani Youssouf,1,2 Catherine Liousse,3 Laurent Roblou,3 Eric-Michel Assamoi,3 Raimo O. Salonen,4 Cara Maesano,1,2 Soutrik Banerjee,1,2 and Isabella Annesi-Maesano1,2,* Paul B. Tchounwou, External Editor

Environ Res. 2016 Oct;150:227-35. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.06.012. Epub 2016 Jun 15. Differential respiratory health effects from the 2008 northern California wildfires: A spatiotemporal approach. Reid CE1, Jerrett M2, Tager IB3, Petersen ML4, Mann JK2, Balmes JR5.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017 May;56(5):657-666. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0380OC. Early Life Wildfire Smoke Exposure Is Associated with Immune Dysregulation and Lung Function Decrements in Adolescence. Black C1, Gerriets JE1, Fontaine JH1, Harper RW2, Kenyon NJ2, Tablin F3, Schelegle ES3, Miller LA1,3.

Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Sep;124(9):1334-43. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409277. Epub 2016 Apr 15. Critical Review of Health Impacts of Wildfire Smoke Exposure. Reid CE1, Brauer M, Johnston FH, Jerrett M, Balmes JR, Elliott CT.

Environmental Health Symposium Wildfire Smoke Challenges and Solutions for Human Exposure. Drs Walter Crinnion and Louise Tolzmann (78 min video) www.youtube.com/watch?v=YIMuAShoaTA&ab_channel=EnvironmentalHealthSymposium&fbclid=IwAR3m7ermnaKMf3LMxkO5inAbiClhLu6glbIAg2lPXlPHtYbQAEx6CIJPYT4

Wildfire Statistics 2000-2019: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10244.pdf