Cara is a 2021 Trail Sisters and The North Face Adventure Grant recipient. This is her adventure story!

Choosing a day for our adventure was the hardest part. My sister, Sima, is a second year medical student. I work in finance in New York City. We both work late into the night and often through weekends. In the little free time we have, we run. Mostly alone, but sometimes together. She lives in Westchester, a 45 minute train ride from the city. When it works, it works.

“What about September 25th?” I suggested.

“That’s the weekend before my exam,” she responded. “What about the weekend after?”

“I can’t,” I remembered I had a work dinner in New Jersey.

We finally decided on October 2nd.

“OK great, and where are we running again?”

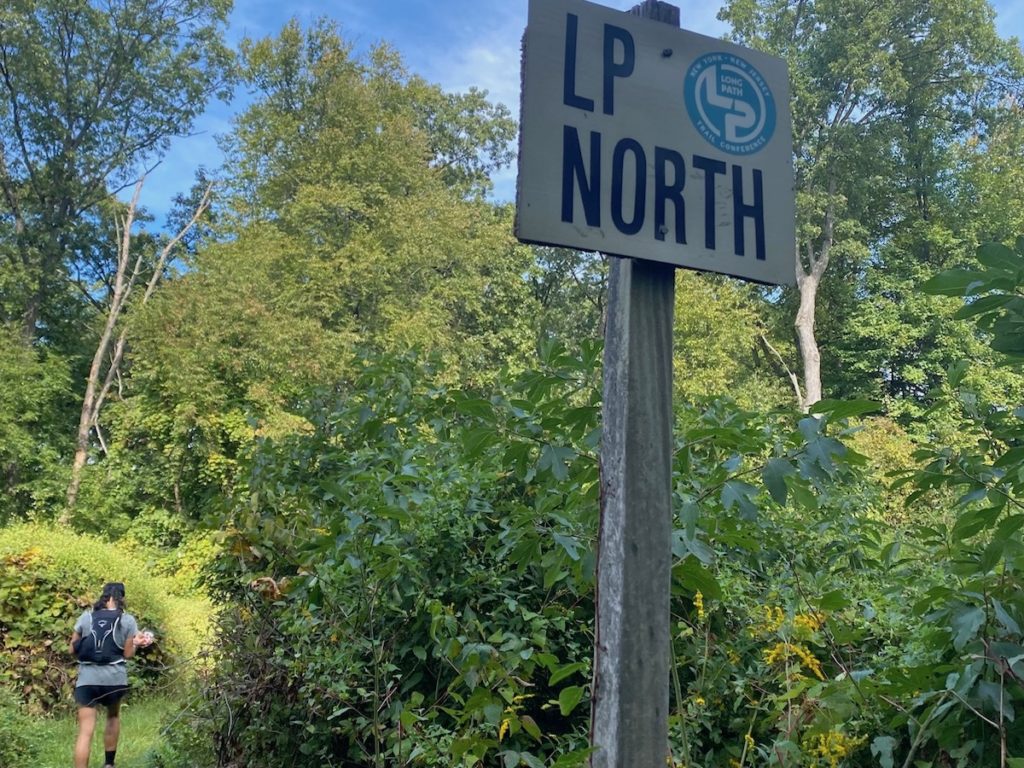

We chose to tackle three sections of the Long Path. The Long Path is a storied 357+ mile hiking trail stretching from the George Washington Bridge in New York City to Altamont near Albany. It runs north into the Palisades along the Hudson River before veering west into Harriman State Park and the Catskills. Maintained by the New York New Jersey Trail Conference, the trail passes through urban, suburban, rural and wild areas on public and private land. It crosses streams, highways, marshes, mountains and forests.

Nyack, a 15-minute drive across the Hudson River from Sima’s apartment, seemed as good a trailhead as any for our starting point. We would spend the day running from Nyack to Long Clove, Long Clove to Mount Ivy, and Mount Ivy to Lake Skannatati, covering Sections 3-5 of the Long Path.

Sima was busy studying, as always, so I put hours into mapping it all out: just under marathon distance with 5,000 feet of elevation gain. I printed the trail map, read through descriptions, and highlighted the parts where we could get lost. When I showed up at Sima’s the night before, she still had no idea where or how far we were running. I carried us to the starting point. Little did I know that Sima would carry us to the finish. I guess we make a good team.

On paper it didn’t seem like a big deal. Sima ran in college and I had just completed a trail marathon in California a few months earlier. College track doesn’t prepare you for mountain running and California trails are nothing like New York’s gnarly trails. We didn’t know what we’d quickly learn once we set out: don’t underestimate terrain and don’t overestimate fitness.

We packed our vests with hydration, fuel and an extra layer in case it got cold at the higher elevations. At the last minute, I threw in a few contents of a first aid kit — some antibiotic ointment and anti venom. “We probably won’t need this,” I told Sima, “but I’ll take it just in case.”

Six or so miles into our run, my shoe caught a rock or a root or a leaf and I fell. Hard. Before I even had the chance to get up, Sima was taking her extra shirt out of her pack. She used it to clean my knee, and I winced as I watched my blood soak through her white shirt. I told her the stain wouldn’t come out. “Who the fuck cares, it’s just a shirt.”

“You’re going to have a nasty bruise,” Sima told me, as she applied the antibiotic ointment to the open wound. She was right; three weeks later and my knee still looks like a plum.

“At least summer’s over so I won’t have to wear shorts,” I said.

“I’m more concerned about injury if you keep running on it while it swells.”

She started explaining something about neutrophils and the acute inflammatory process. Here is where my sister and I are different: she worried about my body and its ability to heal itself; I worried about how my leg would look. She cares about the things that matter. I care about the things that don’t.

We still had 17 miles. So we kept going.

The views of the river were beautiful, the leaves were just starting to change, and the sun was shining. We power hiked the non-runnable parts and rock scrambled the non-hikable parts.

We felt so far away when running under trees and up mountains. We were so geographically close to our everyday obligations, but excel spreadsheets and client meetings and med school lectures didn’t matter out there. The scenery helped, but a sense of adventure comes from within.

Sima and I took turns leading. We spoke about school and work. We reminisced about family trips to France and Kenya and New Zealand. She brought up the time we rode horses in a forest. I asked her if she remembered when, on a bike trip in France, I got off my bike and started crying because my legs were sore. We wondered what our parents were doing at home in Miami at that very moment. We sang our high school song and recited the prayers we were forced to memorize as kids. We fought over the color of the Long Path trail blazes. I said blue, Sima said green. Teal? According to the guidebook I read after our adventure, the blazes are acqua.

At mile 16, we crossed a running stream and I hit a wall. I realize now it must have been a combination of dehydration, underfueling, and denial about the state of my knee. “I want to stop,” I announced abruptly. “Can we just get picked up at the next town?”

Sima knows me and knew that continuing for the remainder of the run would not actually put me in danger and that I was being dramatic. She knew I’d be upset the next day if we were to cut the adventure short. That’s another difference between us: even though she is two years younger, she is wiser. She thinks long term, while I mostly think in the present.

In that moment I was uncomfortable. I was tired. My toenails were in bad shape from the steep downhills, my knee had started to swell, and I wanted to go home.

“I’m tired too, you know,” Sima told me. “I didn’t fall, but my toes are killing me, too,” she admitted. “But we had a goal, and we’re really close. We can have burgers in a few hours when we finish and rest all day tomorrow.”

We walked a few uphill miles in silence.

My mindset shifted. The pain and discomfort turned from something I wanted to wish away to something I just had to deal with. In a strange way, I started to feel grateful for the discomfort and grateful that we were able to keep going even when it didn’t feel easy. I brought this up to Sima after our run, asking if it was crazy to think in that way, and whether she could uncover a life lesson in all of this. She replied “Yeah, it makes you think of the times you couldn’t keep going.” She brought up the time she was pulled out of school for admission to inpatient eating disorder treatment in high school. And how the two brain surgeries she had as a child taught her the privilege of making it through pain. I think I get it. To have the choice to keep going is the greatest freedom of all. Like I said, she cares about the things that matter and has wisdom beyond her years.

I broke the silence to tell Sima we were on our final mile. All 20 of our toes were numb, we were hungry and I had just run out of water. 10 to 15 minutes of running or hiking or scrambling later, we reached the road near Lake Skannatati where we’d arranged for pickup. We made it. The end.

I just sat down on the asphalt. I smiled. I started laughing.

“What the heck is wrong with you?” Sima asked. I couldn’t answer. I just kept laughing.

She started laughing, too, and we sat there in the middle of the road. Laughing to the point of tears. I can’t remember a time I laughed that hard. We couldn’t get words out. What does it mean that when our bodies were stripped of energy and willpower, when we stripped ourselves of unnecessary busyness of life, the simplest common denominator was laughter? I don’t know. But it makes me smile.

We got home, devoured our burgers, slept. The next day, we got back to work. Sima’s nose in her books, my eyes on a desktop, our feet up, our eyelids heavy, and our faces, smiling.

Always, always, always keep going. It’s the only way to make a difference in the world. A smile on a person’s face is a worthy difference. If there’s any point to anything, that’s it.