Call it glorious disappearance. Call it locomotion—Let your body out to pasture. Fill your calendar with nothing but sky.” —Joy Sullivan, Instructions for Traveling West

At 3:30AM in late April, I couldn’t sleep. Fresh off of a string of night shifts, my circadian rhythm had adjusted to being wired through the hours during which—contrary to popular belief—most residents of the city that never sleeps do actually sleep. After frustratedly tossing for a few hours, cursorily reading some Leaves of Grass, and doom-scrolling, I packed a pair of scrubs, my stethoscope, food (meal-prepped oats, PBJs, and pasta), and (for good measure) some bath wipes into my running vest. I then stretched languidly across my rug, refreshing the National Parks Service Grand Canyon website for potable water supply status (still “CLOSED”). At 4:23 AM, decidedly early enough for some New Yorkers to be up but too early for traffic, I donned my headlamp and started my longest long ahead of a taper: a 21-miler around most of Manhattan, ending at the hospital at which I worked to start my shift.

As a still-green resident physician and amateur road runner, my preceding several months had been relentless. I had helplessly watched a close family member suffer repeatedly with worsening illness. I had recently come out of a long distance relationship (with, I should add, a long distance runner who I credit with introducing me to trail), just prior to a much-needed vacation to Maui we were to take together. I had learned from an estimated 3,000 patients in a span of 8 months, performed my first intubations, consumed a gamut of human stories, and gone from a fairly put-together creature of the day to a perpetually discombobulated creature of what-day-is-it?

Because of my work hours, my running had gone from effortlessly social Central Park miles to scrounging for oddly-timed solitary commute runs to the hospital. Home-to-hospital running was always followed by: 1) a cursory wipe-down behind a rather flimsy trifold in our break room 2) a subsequent twelve hour shift on my feet and 3) ravenous hunger with little time to refuel adequately. While deeply grateful for the privilege of doctoring, my able body, and this brief calm ahead of the emergency room’s inevitable chaos, I quickly realized productive speed work was far-fetched. Track sessions followed by multiple all-nighters under fueling would not be beneficial, and I’d probably end up injured. Besides, I found that I was craving longer and longer periods of fresh air and freedom, not to fetter myself further with an unrealistically structured training schedule.

Given the year’s happenings, I was desperate for a “W.” Running for speed or time was infeasible, but running for distance, vert, and headspace was not. I had never run a marathon. I had very little trail running experience. My first, I resolved, would be for myself, by myself, from South Kaibab lodge to the North Rim lodge, across the Grand Canyon. I would baptize my budding inner trail runner with the sweat of crossing “The Big Ditch.” I would create my own Rim-to-Rim training plan around demanding and shifting work hours. Christen whatever accessible vert I could find adjacent to pancake-flat Manhattan. Then: a sacramental solo send, on a random few days off, sandwiched between night shifts. I had luckily snagged the last available South Rim lodging on the first day of the North Rim’s annual opening. R2R—a classic—would certainly feel like a “W.”

The idea had hatched in Maui in February. I had taken the trip independently post-breakup since I wanted to be anywhere but stewing in my apartment, and stayed with an old friend who happens to be a park ranger. He kindly tolerated my intermittent tearfulness, sang along to pop diva power ballads in the car, and pointed me towards Makawao Forest for some soft surface running. With puffy eyes I parked at the trailhead and began. It was my first trail run without my former partner, and I felt the unexpected solitude heavily. But as I navigated the first ascent, weaved through somewhat poorly marked areas, and eventually made my way towards the final switchback, I felt something else: empowerment. I could do this. I really could. A couple of days later my friend suggested running across Haleakala crater. I looked at him nervously; it was about 20 km in 90 degree weather at some altitude (approximately 10,000’), and very exposed. At that time I didn’t own a hydration vest and wasn’t heat acclimated. Thankfully, I’d had a few nights for altitude adjustment (my friend’s loft was a good way up the volcano). With some prodding, I borrowed his Camelbak and tied the straps down tightly, stuck a shirt under my hat for sun protection, and started the sandy descent through Haleakala’s martian landscape.

I saw plants and critters I had never seen before. I saw a fluffy little cloud floating ahead of me and ran through it. I passed through multiple microclimates—broody mist and bright direct sun. Caked in sand, sweat, and dirt, as I hiked out of the crater, I was grinning. If it weren’t for being nearly out of fuel, I would’ve turned back and run to where I’d started. It was adventure, freedom, catharsis, and meditation all at once. (Of course, trail logic ensued). The closest equivalent in the continental US to a steep descent into and out of a hot crater is the Grand Canyon. Perhaps that should be next? My friend had done ranger work there too. “You can definitely do it,” he said. Despite several “you’re insane,” and “people die out there” remarks I got, I chose to believe him. I would respect my body, the landscape, and the weather, of course, and practice fueling and salt intake. I knew I had a solid aerobic base already, I just needed the legs, electrolytes, and a little more technical mileage under my belt.

Just a few stops away on Metro North, Bull Hill near Cold Spring, New York became my ritual. I would take the train, jog to the trailhead, and begin loops of the 6-mile, +1500 ft course. Soon, I got to know the baristas at Citrine Cafe in Cold Spring and started a punch card; a well-timed post-train cortado and pit stop became part of the routine. Since my days off being rested enough for a long trail effort were very numbered, by forcing mechanism I was training on the trail those precious days regardless of sometimes sub-optimal trail conditions. This prepared me for the surefootedness and stability I would need to acquire (and that I certainly lacked—prior to this I thought running across the Williamsburg Bridge was “hilly” and cobblestone was “unstable”). The first time I did two loops of the trail, I was very sore (and very worried that the steep 6,800 foot gain of R2R might be out of my reach). Over the following weeks, along with a healthy dose of strength training, my legs adapted to the elevation gain and I was soon able to do back to back trail and long cycling or running days.

It felt liberating. The antidote to working in a windowless space filled with pathologies certainly was the top of Bull Hill. From there, I could drink fresh air and look back at a hazy view of Manhattan, small and somewhat meaningless from that vantage, before beginning the descent atop loose creekside rocks. With each pass, I marveled at how different the trail looked: leafless, then budding, then flowering. Running pace-agnostically was also new for me, and some initial trepidation subsided into the relief of letting my watch run even if I stopped to tie my shoe.

Once, a friend asked me “what do you think about during all that time alone?” It was a good question. Unlike urban running, I rarely listened to music or podcasts on Bull Hill. “Honestly, just taking the next step,” I’d replied, grimacing at the corniness of my own answer. I suppose I was having the realization that many novice trail runners have: this sport is a lot more cognitively demanding in some ways than road or track. Perhaps that was why I was finding it so cathartic: my focus was on roots and rocks, placing one foot in front of the other, fueling, and following trail blazes. It was nearly impossible to mope. Encouraging affirmations from fellow trail-goers—”You go, girl!” and “badass!”—added to the joy of my self-contained adventurettes.

After one such excursion, when I returned to the 125th Street Metro North station from Cold Spring, I decided to treat myself to a cab ride home. My legs were toasted and I was muddy with a topping of spilled Gu. I hailed a taxi and had it drop me off an avenue away from where I live, which I often do for safety if riding alone. When we reached the destination, I pulled out my credit card to pay.

“Cash only,” he said. In New York, all taxis have credit card capabilities and have to accept card payments. Besides, I only had $2 in cash for a $20 ride.

“I don’t have the cash,” I told him. “I can pay with card.”

“No, cash!” he said, starting to raise his voice. My discomfort grew.

“I only have card,” I replied.

“You can go to a bank and get cash,” he said, “there’s one right here!”

“I don’t have my debit card on me,” I stated. “You have to accept my card.”

He closed out of the digital meter and said “It’s too late, card won’t work now.” What he was doing was floridly illegal, and I felt I needed to get out of the car before he locked the doors, drove, or worse. I opened the door and got out quickly. The driver followed, probably over 6 feet tall and double my weight.

“You can’t leave without paying me!” he yelled within a few inches of my face.

“Sir, I’m going to need you to take a few steps back,” I told him. I was shaking. I clocked a few people nearby, watching the scene unfold. He grabbed my upper arm but I had seen his reach before he could fully grip me. I yanked my arm away and bolted into a book store about 20 feet away. Heart pounding, I took a few deep breaths and tried to calm myself. I just wanted to get home. I texted a few friends in the area for advice, which generally leaned towards alerting NYPD. I didn’t want to call the cops on a guy struggling enough to behave this way over twenty bucks in cash, but at the same time, who else was he doing this to? Even if I did oblige him and withdraw the money, who was to say he wouldn’t demand more? As the minutes ticked on his taxi remained parked outside the bookstore. Why was he not moving?

I gave it ten full minutes. The cab did not budge. I half expected him to come bounding into the bookshop, yelling for the cash. If I tried to exit, he would intercept me. Still tremulous, I walked up to the cash register, staffed by two women. A few other women were nearby, about to get in the checkout line.

“I think I need some help,” I told the cashier, pointed out the cab, and described the situation. By this time, I was admittedly in tears.

“Oh hell no, he can’t do that!” one of the clerks shook her head angrily. “I’ll call the cops,” she said, picking up the desk phone. “We have your back, sister,” the other employee replied. When I turned around I realized the nearby nearly half a dozen women had flocked around me. One had produced tissues from her purse and was handing them to me. Another offered cash. “How much do you need?” she opened her wallet.

“Thank you so much, it’s okay,” I replied, “I don’t know if any of us should be interacting with him without NYPD present.” I felt surrounded and uplifted. If there’s one thing that bands women together in New York, it’s caring for one another’s safety when a man is behaving suspiciously. At one point or another, we’d all been there, and we definitely rally.

When NYPD arrived we orchestrated a strange transaction in which I Venmoed a cop to give the cash to the cab driver. They took down his license and medallion number and handed it to me “if I wanted to report his behavior.” I understood their desire to minimize paperwork. Even after the cash had been given to him, the driver stayed parked by the curb. NYPD was about to leave. The store clerk rolled her eyes. “Boys, she’s not leaving this store until he’s gone. You need to tell him to get going.” They obliged and the cab driver pulled away. “Call us when you get home,” she said. I thanked her profusely, walked home, called her, and thanked her again.

“Of course,” she said, “we’ve gotta look out for each other.”

The encouragement continued. A few days before departure, my wonderful colleague coming onto a night shift caught me on my way out, extracting a safety beacon and headlamp from his blue Patagonia backpack. More than he probably realized, I was touched by the gesture of support (and grateful to have a headlamp more high-powered than my existing urban-running one). Despite being well-trained, I knew there were many potential factors out of my control, and feeling like there were people (and an easy-to-use beacon) in my corner helped soothe some nerves. My plan was to make it across the canyon in time to eat a massive lunch and catch the last shuttle from North Rim back to South Rim, which left at 2PM. If I didn’t make that, well, I would have to figure out a last-minute tent situation.

At the airport in New York, I chanced upon Joy Sullivan’s Instructions for Traveling West book of poetry which aptly portrayed the call of trails, love and heartbreak, woman-specific notions of beauty and body, work-life tensions, and even talked about being a third culture kid in Ohio (all too relevant for my Ohio roots). I felt like I’d been gifted a manual for processing my muddy thoughts. “Commit to the road and the rising loneliness—take the trail that promises a view—bruise your knees—keep going” she instructed. “Pet trail dogs,” Joy added. I had hardly read for pleasure since starting residency, and felt grateful for the opportunity to engage with her work.

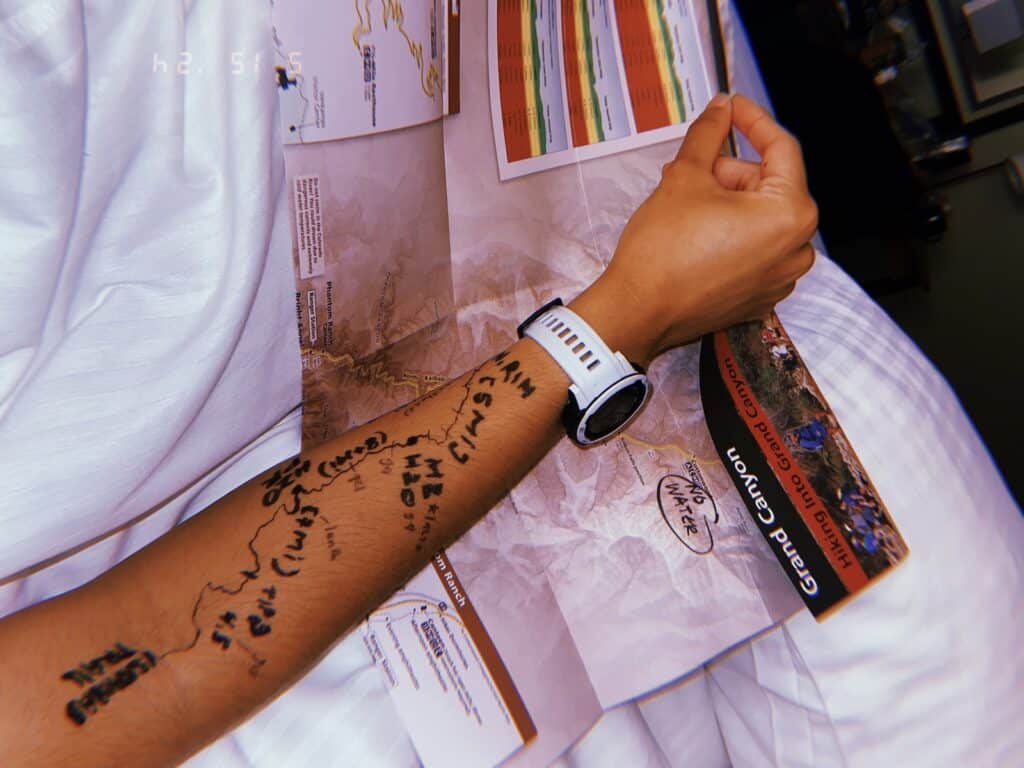

When I reached Phoenix, I rented a Mini Cooper convertible. It was only a few bucks more than the base sedan, and hey, the tax return had hit the bank account. I listened to music and podcasts and caught up with old friends over the phone. I did a shakeout run in a forest near Flagstaff. I picked up groceries. As I pulled into the Grand Canyon park area, it had started to rain. It was a gentle, rare sprinkle; the drops landed silently atop pine needles, creating a fragrant cool that felt like a blessing ahead of the next day’s effort. I stretched. Refreshed the inner canyon water status: OPEN. Ate pasta. Drew a map of the water along the trail on my arm and committed it to memory. Laid my clothes and gear out for the morning. Set my alarm. Felt the hymn of pulse moving through my limbs. Closed my eyes. Slept deeply.

—

For Dr. Maddie Giegold, whose contributions to Trail Sisters ended far too soon but continue to inspire honesty, introspection, and a bright love for the outdoors.