In many ways, my athletic career has been defined by a sound: POP! 5 of them to be exact. Not always the same POP, like the variation in crackle of twigs and leaves, but a harbinger nonetheless. A harbinger of an end, of a beginning, of a long road from injury to recovery. There was the first ACL; the first meniscus tear; the first MCL tear; the second ACL tear; the second meniscus tear. My left knee has born an unfair share of these burdens (as in, ALL of them). My right knee got to play the role of healthy donor sibling for the 2nd ACL surgery, but beyond that, has stood innocently by while my left knee has gone through hell—so much hell that I decided I needed to run away from soccer. As it turns out, running proved to be a fabulous answer for a decade.

Injury free, I marveled at the resilience of my left knee. Then, practically out of nowhere, my dog changed everything. Dogs are not known for their spatial intelligence; and within the dog world, my love of a lab would score LOW. Therefore, it is not altogether surprising that he did not perceive my planted left leg as something that he should go around. I am not sure he even understood his role in the shockwave that sent me crumpling to the ground. The pain was sharp, and was accompanied by the dreaded POP! As the initial pain dulled, my rational mind was able to return to my skull, and help me assess what had happened. POP=bad. But I knew it wasn’t that pop, so maybe it wasn’t so bad.

I spent a few weeks doing what so many athletes do: ignoring it, and hoping it would return to normal. I found walking to be way more painful than running, which I decided was a good thing, because it meant I could still run. I iced. I ran. I watched. After it became apparent it was not going to miraculously heal itself (I know, still shocking after all these years!), I knew it was time to seek care, but what care? Finding healthcare professionals who treat knees AND think that running is not the worst possible form of exercise is a challenging task. Luckily, Portland is home to Evolution Healthcare and Fitness, a comprehensive integrated healthcare and fitness mecca. I’d like to say that I wasted no time in scheduling an appointment (because if that cliché were true, I would be so much farther along in my recovery), but when I finally did decide to seek expert help, Evolution was where I started, because I knew that if there were a non-surgical answer to whatever wreckage my dog had unleashed on my knee, the practitioners at Evolution would know that answer. I also knew that their first step would not be to take running away from me (yes, I say it like a kid being grounded from electronics!).

My first appointment started with good news: all major ligaments were intact. Hallelujah! Then paraded the bad news: the meniscus had not fared so well. Meniscus is particularly fickle when it comes to healing, because so little blood flows to the tissue. As a result, damaged meniscus can be like purgatory, never as debilitating as a torn ligament, but never healing either. Surgically, the response is generally to cut away the damaged meniscus—discard rather than repair. No one is ever excited for surgery, and a surgery with mediocre results is even harder to meet with enthusiasm.

Then came what I would come to embrace as both good and bad news. My Sports Chiropractor, Dr. Brad Farra explained a non-surgical promising protocol that he recommended for treating my injury: Blood Flow Restriction Therapy. I would quickly learn that the good news of side-stepping surgery meant plunging instead into a unique form of torture. Luckily, like most MUT runners, I have a hampering for Type 2 fun, and before long I learned to look forward to my weekly torture session.

According to Dr. Farra, “Personalized Blood Flow Restriction Rehab and Training is an evidence based technique in which a specific pressure is used to reduce blood flow to an extremity while performing an exercise at a low load. The effects are that of muscular strength and hypertrophy (growth of muscle cells), and connective tissue (ligaments, tendons, fascia, cartilage, fibrous tissue, bone) healing through a hormonal response.” The real benefits of BFR can be best understood by anyone who has ever shrieked in horror at their withered muscles following a surgery; it seems no amount of strength training prior to surgery can stave off the dreaded atrophy. But not so with BFR. Dr. Farra explains, “When specifically dealing with an injury, BFR can be used to maintain and even increase strength above baseline while rehabbing an injury.” BFR can be used to strengthen the muscles that might be involved with sprains, strains, plantar fasciosis, shin splints, achilles tendinopathy, ilito-tibial band syndrome, and other common running injuries.

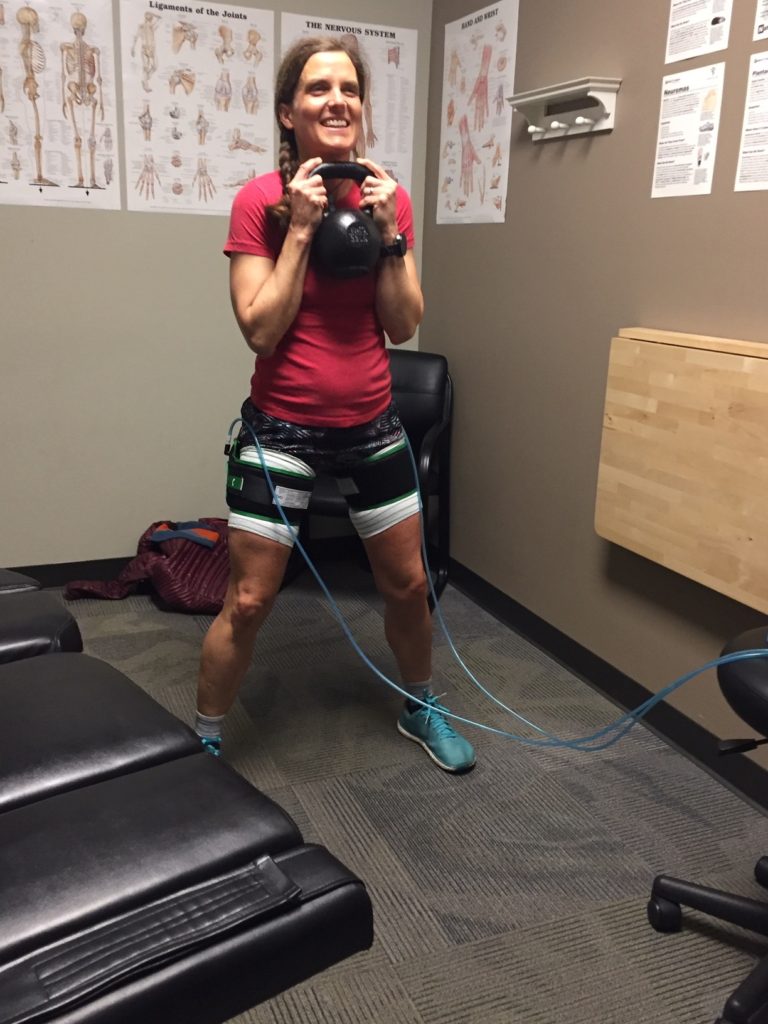

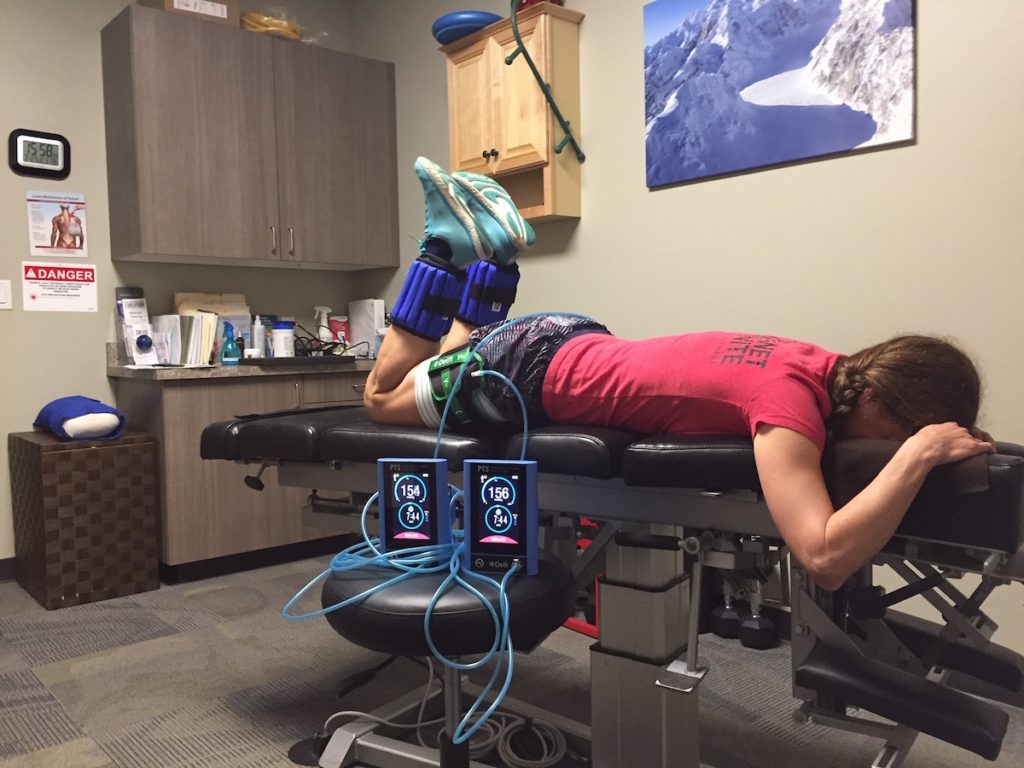

In practice, it looks like doing strength exercises with large blood-pressure cuffs that restrict blood flow to whatever area you are targeting. More important than what it looks like is what it feels like. The restriction of blood flow causes a set of air squats to feel like truck squats (as in semi-truck). My first session left me humbled to say the least (demoralized and licking the wounds to my self-esteem if I want to be more honest). I barely survived a set of 30 squats, followed by 3 sets of 15. Air squats. Not exactly an accolade on the resume of a mountain runner.

Little by little, it has gotten better. I have done BFR almost weekly for 5 months. I can now complete the squat series with a 10kg kettle bell (I know, HUGE!). I can also survive the hamstring curl series with “massive” 5 lb weights on my ankles (the first time I tried hamstring curls, I did not even make it through the first set of 30, with no weight, which exposed an endemic weakness in my hamstrings, which as happens for so many runners, my quads compensated for). Dr. Farra has observed an increase in my quad, calf and hamstring strength, as well as increases stability at the hip and foot.

These changes have not come rapidly. There are certainly weeks during which I questioned whether I had made the right decision to pursue an alternative therapy rather than a traditional surgical solution. After 5 months of treatment, I am not completely healed. That sort of slow progress can make room for plenty of doubt to sidle in and take up residence in my mind. But when I can zoom out and view my trajectory with perspective, here is what I know:

- I have never skipped a run due to this injury. I have run up and down and around mountains, all while slowly but surely rehabbing my injury.

- When I started BFR, I was at my normal strength level as a runner; yes, I had pain, but I was not physically weakened by the injury. I never had to start from the radically weakened position of atrophied muscles that come from invasive surgery.

- I have less pain, more mobility, and more strength in muscles, joints and tissues crucial to my long-term running joy.

I do not know what the “end” looks like. I know that right now, I am continuing to improve. Will I be pain free? I don’t know. Will I continue to feel pain from quick extension or hyperextension of my knee? I don’t know. I hope not. I am fairly confident that this journey is going to end with me a stronger, healthier runner, but I also know that in many ways this is an experiment for me. For now, the results plot a line of positive improvement, so I will continue the trudge up the hill, and trust that there will be a summit worthy of the climb.

Feature Photo by Sara Pedrosa