How changing my running mindset led to a healthier life outlook.

In the winter of 2019, I set out to check off a new personal record by running 10 kilometers in under 50 minutes—a feat I would perform at Oxford’s Town and Gown 10k in May. This was following on from a successful half marathon training cycle where I beat my sub-two hour goal time by nine minutes.

In parallel, I was performing experiments for my PhD which required regimented scheduling of laboratory timepoints. I was dreading several months of daily lab work, but I focused on the outcome of obtaining a doctoral degree. Drawing up a running training plan was a natural extension of my unflagging student self.

Race day arrived after twelve weeks of laps around the track, hill reps, Fartlek interval training, and two visits to a physical therapist to deal with tight right calf muscles. Within the first few kilometers I was not hitting my race pace split times. I felt exhausted and a side stitch under my ribcage held me back from performing at my peak. But for the sake of meeting my sub-50 minute goal I gritted my teeth and chased after the time, causing even more pain. With less than 1 kilometer until the finish line, the side stitch intensified and I told myself I would just run all out for five more minutes and then I wouldn’t have to train for a road race again. I crossed the finish line with half a minute to spare but felt miserable and unsatisfied. The pursuit of this arbitrary goal time led to several weeks of not being able to enjoy running. I left the race village with a medal around my neck, but also with a lingering cramp and confusion about who I was as a runner. If I’m not chasing faster paces am I doing anything productive at all?

A women’s running retreat in Iceland three months later helped answer that question. Through mindful running workshops and scenic routes in glacial valleys, I learned to focus on intentions rather than goals. We discussed how many runners are strictly outcome-oriented, setting mileage and pace goals. Mindful running calls us to switch to process-oriented thinking: how running makes us feel. During one workshop we were presented with a list of over a hundred key values and asked to choose three words to describe what running means to us. The terms “adventure,” “committed,” and “joyful” jumped out at me. My running identity crystallized as we huddled cross-legged with worksheets on our laps and bunks in our volcano hut at Þórsmörk. I realized that I run to explore, I run to show up to something consistently for myself, and I run to feel childhood glee again. While the value of commitment was evident in my consistent training, I had been lacking adventure and joy for several months.

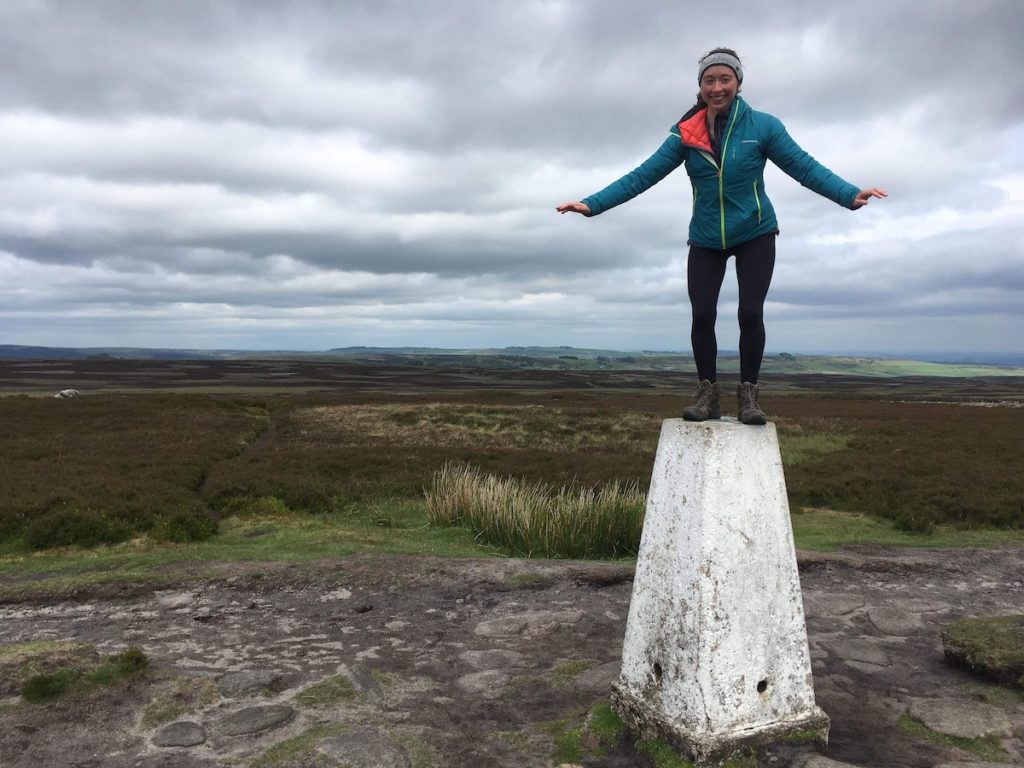

Upon returning home after a week of trail running and power hiking bliss, I grappled with how to balance my values. I decided not to make any training plans for a while and not sign up for any road races. Since I couldn’t set aside the outcome-oriented focus of pursuing personal bests on road races, I refocused on a half marathon trail race in the Lake District—an event that would have me admiring scenery and paying attention to roots and rocks rather than fixating on my Garmin watch.

Towards the end of my PhD, I felt the same way as I did after the 10k race. I had met a huge milestone (1.6 kilometerstones for metric system readers), but I was feeling unfulfilled and demotivated. Thinking the issue was a result of my research field, I pivoted from experimental biology to science education and enrolled in a two-year educational research master’s program. As in my running training, I was showing up consistently and performing near the top of my abilities. During the first semester I realized my lack of motivation might not be a question of the subject matter but the academic environment. I grew tired of submitting assignments that would be graded against an answer key. I felt like the reports and exams were herding me away from my creative, risk-taking tendencies towards responses that could be easily verified in a grading rubric.

I have been enrolled in school and university for over two decades without a gap year or chance to try out a more conventional 9-to-5 job. Unsurprisingly, I spent months thinking about if or when to leave the master’s program. In the second semester, I realized that I was mostly staying because I didn’t want to disappoint the lecturers, my peers, or a hypothetical future job interviewer. I imagined the interviewer scrutinizing a gap in my CV and asking why I did not have the stamina to finish a two-year program.

Before I imagined my hypothetical answer to the hypothetical interviewer, I had to search within myself for my motivations. My running story proved illuminating. I saw my PhD as my painful 10k race: I had met my goal time but had trudged through the monotonous training and lost my sense of adventure, creativity, and joy in the process. This master’s was now a 2-mile time trial. Based on my prior training for 1 mile and 5 kilometers I knew I could train to get a 2-mile personal best time, but I didn’t want to submit myself to the pain and tedium again. I yearned to flow over trails without thinking of paces or distances, granting myself the ability to admire panoramas and birdsong.

With my sense of purpose clearer, I knew I was done being a student, but I was not done learning. I was suffering from academic burnout, and a counselor confirmed this.

In running, we can listen to our bodies as a cue to calibrate our effort. Push too hard and you might get sidelined with an injury. But why do we pay more attention to bodily pain symptoms than mental burnout signals? Completing a PhD thesis and several assignments, reports, and exams for my master’s was completely draining, but I kept going because my grades were evidence of high achievement. I was letting the good feedback from professors and peers drown out the chronic signals of demotivation and dissatisfaction my brain was trying to send.

The grades were like the goal times I set for myself. Getting good grades convinced me that I was doing well and should keep pushing, but I had to stop and listen for symptoms of injury that no one had taught me how to recognize. “Doing well” in terms of quantitative grades and goals is not an indicator of doing well with qualitative wellness.

I am now leveraging the mindset I’ve employed in my running journey – to move from focusing on outcomes to noticing how a process makes me feel. Therefore, I decided to leave my master’s program in the second semester. I knew I could work hard and complete the degree but that it would leave me exhausted and unfulfilled come June 2022. I viewed the second year of the program like Track Tuesdays. Just as pushing myself to my anaerobic threshold during track intervals was difficult, the training was not necessarily challenging me since I followed the instructions on my plan and made dozens of left turns. This master’s program had me studying at the limits of my workload capacity and I did not feel excitement knowing my future tasks were planned out on a syllabus.

Over the years, the 400-meter track on Iffley Road has given me familiarity that eventually turned into predictability and left me wanting more adventure in my running. Recently, I have felt the same about the “academic track.”

Trail running has brought excitement to my running routine. Even familiar trails have an unpredictability that excites me—keeping me curious about whether fallen branches have moved, stones have shifted, and if floodwaters will divert me or be an aquatic part of my route. In the woods and fields, the path is not always evident across seasons and this fills me with a sense of adventure and agency in forging my own path. I realize the risk of tripping over roots and rocks is higher while running on trails versus a track, but that’s a stumble I am willing to take if it brings me to a flow state and leads to inspiring panoramas. Even though I have not felt motivation and excitement throughout all of my running and academic training, I don’t regret these experiences. Both have taught me about the capacity of my body and mind, refined my sense of what I enjoy in life, and have led me to the start of a new adventure.

I am not sure where the next year will take me since this is the first time I am heading into new territory without syllabi or academic terms. However, I do know that I will listen to signals of what excites me and look for opportunities where I enjoy the working process—something I’ve already started feeling in writing this essay.

And to the hypothetical job interviewer: I am prepared to answer your question about a time I quit something and why.