Part 1 – The Decision to Run

“Beginning of the 2024 Cocodona 250…….. Let’s Go!” Corinne Shalvoy’s voice rang out on the livestream as runners surged over the start line, their headlamps slicing through the predawn haze in Black Canyon City. I was watching live from a world away, steaming through the Caribbean Sea aboard a Coast Guard cutter, on a mission to deter illegal migration and drug trafficking before it reached America’s shores. Still, I felt the electricity of the race, the same charge powering runners forward and engaging thousands of people watching online from around the world. Over the next five days, whenever operations allowed, I sat at my desk bracing my core against the rolling seas, listening to the Cocodona 250 livestream playing in the background while I worked. A similar scene has played out over the last several years. Lags, pixelated images, and all, I’ve loved watching the live coverage of the race. Not because I was cheering for anyone in particular, but because I was cheering for everyone. Having done a few 24 hour races, I had a taste of what it was like to push through pain and fatigue to achieve a goal. Watching others do the same let me feel like I was siphoning some of that struggle and joy into my own life.

And then the 2024 Cocodona ended. The final two finishers crossed the finish line and the broadcast ended. My routine returned to normal: early wake-ups, workouts before the Caribbean heat got unbearable, daily operations, endless paperwork, meetings, training – rinse and repeat. Don’t get me wrong—I love going to sea. But after Cocodona ended, I felt the letdown and knew exactly why. For years I’d dreamed of races like Cocodona, Moab, or Western States. But I’ve never signed up. The reasons always stacked up like mountains: not fit enough, too expensive, too much time away from family, medical issues, unpredictable military schedules… life in uniform rarely lends itself to advanced planning.

So each year, I did the practical thing. I told myself, Maybe next year.

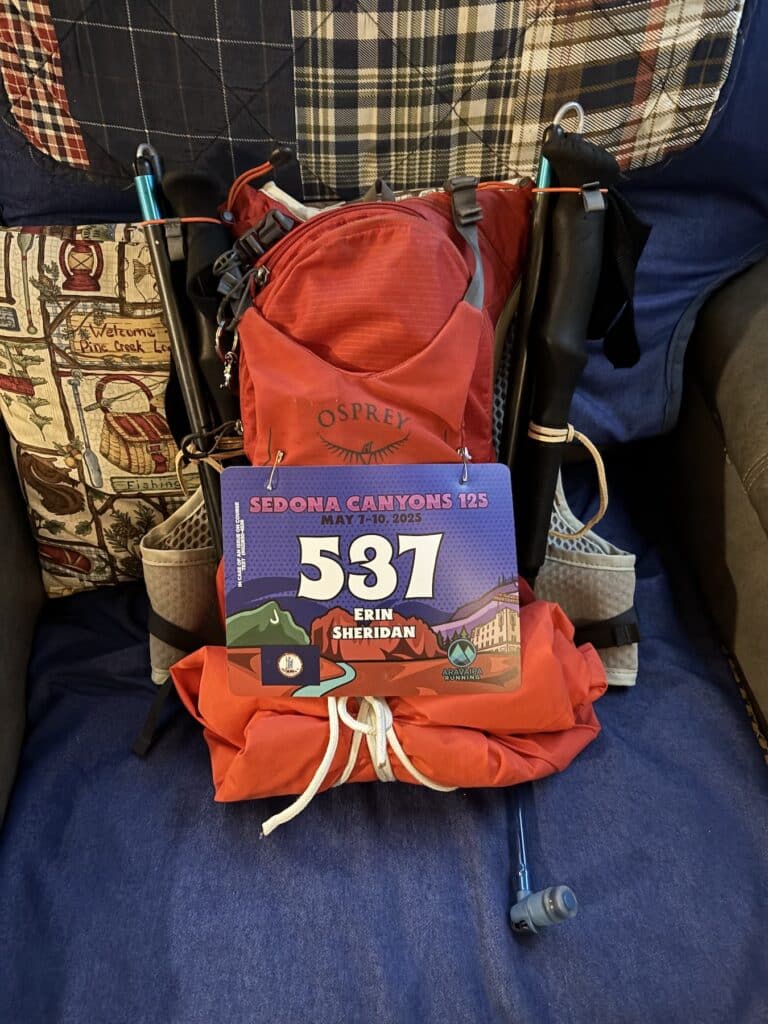

But in 2024, something shifted. I realized I was waiting for the perfect moment that might never come. Maybe the challenge wasn’t just on the trail—maybe it started long before the first step. Maybe this was the hard part: saying yes even when life wasn’t perfect. So I did it. I clicked “Register” for the Sedona Canyons 125. I still was at sea and couldn’t run except laps around a tiny flight deck, but I started training the best I could.

The theme – doing the best I could – followed me home. Once I rotated into an onshore post, training meant squeezing runs into odd corners of the day: between commutes, before sunrise, between cooking dinner and shuttling my daughter to dance and Scouts. It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t perfect. But progress happened.

Then—setback. Emergency gallbladder surgery. One month off. That sucked. But I sucked it up.

I got back to work. I finished two 50Ks, slower than I’d hoped. Then my first 100K—crossing the finish line just minutes before the cutoff. Each of these finishes were hard-earned victories, and I celebrated them. But doubt lingered. My weekly mileage wasn’t where it “should” be. I hadn’t dropped the weight I wanted to. Still, I was committed. I read race reports, devoured YouTube videos, and annotated the runner’s guide like a college textbook. I built spreadsheets with projected paces—slow, moderate, wishful thinking. I booked my flights. It was happening.

Two weeks before the race I had an orthopedic follow up for a knee issue that had been giving me twinges for years. I’d finally been approved for an MRI and was meeting the doctor to go over the results. As it turned out, my right meniscus was pretty wrecked – complex radial tears, extrusions, a cyst, and some bone bruising. Scary sounding stuff, and this was supposed to be my good knee (my left ACL had been torn and reconstructed in 2020). A few deep breaths and a lot of questions later, I realized that the world hadn’t changed. The doctor hadn’t given me any red lights, just a reality check that my knee (like the rest of my body) was slowly wearing down from years of hard love. This more precise knowledge about where the pain was coming from didn’t change a thing. I knew going into the race that I had risk from various medical issues. I’d learned to accommodate them through training and technique. Yes, there was a chance I could catch a meniscus flap during the race and lock up my knee, but that same risk existed walking around my house. I couldn’t let fear and uncertainty, like they had so many times before, keep me away from what I knew I could do. So I went.

Part 2 – The Start

I found myself standing in the start corral for the Sedona Canyons 125. The ground was soft and muddy from days of unseasonable rain, but the crowd buzzed with energy and anticipation. Years in the military had taught my mind to focus amid chaos, but I was so amped up that I had trouble remembering to put on sunscreen. Just outside the fenceline my dad stood watching, looking proud and excited. He had volunteered to crew me for the race, driving all the way from Florida with my mom in their travel trailer to support me. Music thumped in the background. The race director said something inspiring, though for the life of me I can’t remember what. And then… we were off! I could imagine the live stream hosts commentating and people from far away watching this moment just like I had, dreaming of when it would be them.

We poured out of Jerome like water down a hill, spacing out over the decent into the Verde Valley. Every so often a light blue bib marked a Cocodona 250 runner, and we’d offer words of praise and encouragement as we passed on fresh legs. In Clarksdale, parents and children on their way to school cheered us on. The Verde River Crossing, so often featured in Cocodona photos and videos, passed quickly in a refreshing and fast flowing blur. With soggy shoes we squelched through the cottonwoods, rose into the mesas, and crossed the mat into the first aid station at Dead Horse State Park. I checked the cheat sheet tucked in my pack. I was a little ahead of my ‘moderate’ pace time and feeling strong. I grabbed my drop bag and some snacks, found a seat next to the fire, and tried to make quick work of a shoe change and gear refill. In the calm of my home, 20 minutes felt like a sufficiently adequate time but in reality, it flew by in a flurry of activity. Oh well, a 30 minute turnaround wasn’t too bad.

The 13 mile stretch to Deer Pass was where the race began to feel real. Gone was the giddy adrenaline rush. Now was the time to settle in, find my pace and stick to the plan. It was also my first look at the people comprising my general pace group, with whom I would be playing a long game of leapfrog over the next two days. It surprised me how varied everyone was, with no single body type or common age range. Old to young, slim to stocky, everyone was different but the stoke was universal. As we moved across the desert with a shared purpose, we talked. I found that one woman was racing to honor the memory of her brother killed in combat. One man was running just because his wife thought he couldn’t do stuff like this anymore. Others didn’t share their why, but wanted to talk about the weather, where they were from, their favorite national park, and so on. Talking passed the time, and though I am an introvert naturally, I enjoyed these fleeting encounters. It grounded me, and made it all more human.

I pulled into Deer Pass Aid Station 20 minutes after my ‘slow’ time prediction. I tried to keep my gear change and food munching more contained this time, but 28 minutes still ticked by before I was off again. Gaining ground towards Sedona, I realized I’d severely underestimated how much the terrain would slow me down. In my 20s or even 30s I would have bounded over the basketball-sized boulders like a mountain goat, but after destroying my ACL tripping over pavement (of all things) I had a deep respect for uneven terrain. My temperamental right knee only added to the caution. The consequence of selective running was a slower pace and I was falling further and further behind schedule. The negative self-talk was creeping in. The spreadsheets. The “shoulds.” The silent pressure to prove I was good enough to be out here. But then – I let go. I let go of my paces and perfectionism. It didn’t change anything about how hard I pushed myself, but when my perspective shifted the gratitude and joy came back. And that changed everything.

I ended the leg feeling strong, running the last mile along the smooth, lamp-lit streets of Sedona into the aid station. It was the first time seeing my dad since the race had started almost 14 hours ago. Squashing the guilt I felt for how long he’d waited, I smiled as he cheered and directed me around to the check point. I sank into his chair and gobbled down food while he went to work taping up my feet. It was his first time crewing me. With our Type A personalities we naturally clash, but once we acknowledged that our exchanges were going to be blunt out of tiredness (not rudeness), we managed just fine. Though I knew I could have run the race without crew, I was so grateful to have him there. He held up a towel so I could change into dry, warmer clothes, refilled my hydration pack, and in general was a steady, encouraging presence. 40 minutes later at 9:30 pm, I headed back out into the lamp-lit streets of Sedona.

Soon after I was across Oak Creek (grateful to the reroute that kept our feet dry) and back onto the trails. The night stretch through Hangover Trail was eerie and magical. I’m no stranger to running alone at night, but was well aware I needed to keep my wits about me on this section due to exposure. At night, the world shrank to the beam of my headlamp and the faint outlines of rock walls against the star-filled sky. I found that I couldn’t see the drop offs as much as feel them. When a large expanse of nothingness stretched just beyond the sloped trail, the vastness of space felt different on my skin than the air closed in by trees or canyon walls. Aware of the consequences and really not wanting to get lost, my eyes constantly scanned for the next rectangle of white paint on red rock. Then the trail made an abrupt right turn directly up the slope and a grin split my face. Keeping my poles together in one hand, I scrambled my way up the slickrock, trusting the friction of my trail shoes and gripping the sandstone as needed. I would have loved to have seen this section in the day, but the night added a unique twist. It was one of the most memorable parts of the race.

Eventually slickrock gave way to gravel road, and the task at hand became the tedious grind of climbing up the plateau. Near the top, I was surprised to find myself suddenly surrounded by other runners. After hours alone, it was a welcome change to be in a herd of chattering people. Where else can you be in the middle of nowhere at 2 am, walking briskly to keep warm in near freezing temperatures, alternatively cracking jokes and reflecting on your life with a group of faceless strangers lit only by headlamps? I love ultrarunning.

At 3:10 am I strode into Foxboro Ranch Aid Station, a brightly lit open barn with numerous fire pits and lots of people. Grabbing a bowl of steaming oatmeal from the friendly volunteers, I found a chair where I was practically sitting in the fire and tried to coax some warmth back into my fingers and toes. Dad found me a little while later, and after refilling my pack with essentials, we moved to the truck where I gratefully climbed onto the rear bench seat lined with blankets and pillows. The truck was warm and it felt heavenly to lie down. After checking out with the aid station, we left Foxboro to shuttle to Crystal Point Trailhead, a short 6 miles down the gravel road. Although the Cocodona 250 runners continue on foot, the Sedona Canyons 125 runners took a short shuttle detour to limit interference with Mexican Spotted Owl nesting grounds. Snuggled in my warm cocoon of blankets, I certainly wasn’t complaining. I managed my first few minutes of blissful sleep, then opened the door to the pre-dawn chill and another day of running.

Part 3 – The Grueling Middle

The experiences of the next day of all blend together. We were now in the ponderosa pine forest of the plateau. The spacing of the trees meant that even though I was surrounded by forest, shade rarely graced the trail. It was hot, dry, and dusty. The longest gap between aid stations, 18 miles, was also in this section. Combined with the accumulation of miles and lack of sleep, it was a grueling day. Additionally, I failed to do math correctly to account for how long it would take to arrive at Fort Tuthill, the next place I would see my dad. Consequently I arrived at Homestead aid station (mile 84 with 15 miles still to go to Fort Tuthill) just after sunset without a warm jacket or a fully charged headlamp. Being at 7,000 ft elevation, the temperature plummeted as soon as the sun set. I found a chair inside the relatively warm medic tent to assess my situation. Several runners were crammed inside, sleeping on cots or the dirt floor, wrapped in whatever they had available and trying to capture a few minutes of sleep. Overall I felt fortunate to be feeling ok. I was tired and my feet ached something fierce, but I was still moving well and feeling strong. However, I was very concerned about my ill preparedness. After 36 hours of racing, I knew my body would not be able to generate sufficient heat to keep me warm for the six to seven hours it would take to reach the next aid station. After some consideration, I took out my space blanket (a mandatory gear item) and using scissors and tape from the medic, fashioned a tunic. I put it on over my jacket and under my hydration vest, securing the loose materials as much as possible. I made loud squishing noises with every move and looked like a walking baked potato, but I was warm.

The next leg to Fort Tuthill was easily the lowest point of the race for me. The trail wound through sections of freshly harvested trees, turning this way and that, resulting in total disorientation. I could not tell if the lights from other racers were ahead or behind me. Because this section was re-routed after the race started, my GPS file did not match the course, and the forest floor was so littered with logging debris I couldn’t be certain I was on trail. Then my headlamp died. I was too tired to be angry about it. In the dark I took off my pack, rustling in my baked potato parka, and found my portable battery charger. I plugged in the headlamp and turned on the charger’s small, dim light. Moving slower now, I carefully scanned left and right, low and high, as to not miss a race marker. After an hour, I unplugged the charger and turned my headlamp back on. Gratefully, it worked, but I kept it on its lowest setting. The trail kept twisting and turning, always onward but seemingly going nowhere. That’s when the anger kicked in. What kind of game was the race director playing? Why did he have us running in endless circles? As my fury built I realized I was choosing it, using anger to drive me onward and as a distraction from the sobs growing in my chest. I was hurting, exhausted, and frustrated. I wanted to collapse into a puddle, but because I couldn’t I stoked the pain into an anger that fueled me for the next couple of miles. Finally (finally!) the trail descended to cross under the freeway then climbed up the other side and into Ft Tuthill. It was almost 2 am, and that section was my slowest pace of the entire race, but I made it!

My dad greeted me as I crossed into the warm warehouse that hosted the Aid Station. I grabbed a huge plate of pasta and meatballs, sank into a chair, and proceeded to chow down while regaling my father with the stories of the day. The aid station was quiet, just a few other runners and their crews. A massage station over in the corner looked inviting but I had an elemental need for sleep. Plate finished, I hobbled over to the truck, gratefully removed my shoes, and climbed into the plush embrace of blankets and pillows. I asked dad to wake me up in an hour and sank quickly into unconsciousness around 2:20 am. I woke an unknown time later to dad’s snoring from the front seat. It was still dark out, but …. Oh my goodness it was 4:30 am! Shaking dad awake, I found my headlamp and as quickly as I could went about prepping my gear. So much for that massage, I needed to get back out on trail! By the time everything was ready pre-dawn was glowing in the eastern sky. I gently set my feet down on the pavement and gingerly walked a few steps. The stiffness quickly departed and I felt surprisingly good. Waving to my dad and encouraging him to get more sleep, I started out at 5 am. A few strides later I was running. This felt amazing! The air was crisp and energy surged through my body. I was 100 miles in. 30 more to go!

Part 4 – The Finish and The Horizon

The renewed energy wore off a few miles later, but the positive boost it gave remained. The snow-capped peaks of the San Francisco mountains loomed overhead. Soon more and more houses were appearing alongside the trail. The signs were clear. We were in Flagstaff! The course turned onto neighborhood streets. Soon the first runners of the 38 mile Flagstaff Crest race began passing me, full of speed and smiles; I wondered, Is this what we looked like to the Cocodona 250 runners when we left Jerome two days ago? Before long I was striding into the last aid station of the race. A pulled pork sandwich and quick refill of supplies later and I was back on trail. The finish line was only a mile and a half away as the crow flies, but the course would take us on a 13 mile “victory lap” of Flagstaff. Climbing up onto the plateau north of the city, I was pleased to share a mile with a racer I’d run alongside the first day. After she forged ahead, I hailed out to another racer who had accidently veered off course onto a social trail. He caught up to me a short while later and we spent the next few miles distracting ourselves from pain with conversation. Every rock, every piece of shade covered ground, had started calling my name. My mind knew it was impractical to stop so close to the finish but I was losing the battle with my body. If it wasn’t for the company of another runner, I would have stopped for certain. Did I care about my finishing time at this point? No, not really. I could have stopped to rest. But I wanted to cross that finish line knowing that I’d given it my best effort. I was deeply grateful for a friend to help keep me going in those final miles. I now understood why pacers could be such a gift.

At last the trail turned, weaving back into neighborhoods. The rocks disappeared (yay!) and the surface softened into finely ground gravel as the trail flowed alongside the Rio de Flag. This was it, the final stretch back into town! A grin spilt my face and an amazing transition occurred. The pain I had been fighting against for so long disappeared replaced by pure joy radiating through my body. I couldn’t contain myself; I broke out into a run. It felt incredible. I felt incredible. Texts from my husband and parents came chiming into my phone. “Almost there. YAHOO! You’re doing great!” wrote my mom. “HIT IT!!! Home Stretch! You got this! Big push!” came from my husband. I knew they were both glued to the live stream, watching my little tracker icon move closer and closer to the end with each update. They had been my cheerleaders all along, and I felt them there with me as I kept running, miraculously, towards the heart of Flagstaff. All at once the course rose from the river trail and I was on city streets. People drinking beers and chomping burgers were cheering loudly from a brewery. Locals walking the sidewalks clapped for me and pointed the way. For years I had watched other runners hit this final stretch of the race, dreaming of the day when it could be me. Now it finally was. I saw the corner coming up, that last turn into Heritage Square. My eyes started tearing up as I ran around the bend and saw the finish line. The square was packed. I heard the announcer bring everyone’s attention to my approach. The crowd broke into a chorus of cheers and cowbells. I ran strong across the finish line, my fist punching towards the sky, and my face wet with sweat and tears. I had done it!

For a moment I was overwhelmed with emotions I didn’t know how to express. My eyes scanned for the live stream camera. I looked into it, tapped my heart, and pointed at the camera to send a silent message of love and gratitude to my husband and daughter. A volunteer came up to me, saw something in my face, and wrapped me in a hug before gently removing the spot tracker from my vest. She then handed me a belt buckle. Holy crap. I found my dad standing just beyond the barricade and ran over to him to give me a big hug. No one else was coming in at the moment, so I dragged him out to the arch for a quick picture. After that, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I wanted to jump and scream my joy. I wanted to sit down and rip the shoes off my feet. I wanted one of those burgers and beers I saw folks enjoying. Torn by indecision, we stayed for a few minutes to watch the next finishers. I recognized most of them from sharing miles on the trail. They all reacted differently as they crossed the line; some appeared numb with shock, others shouted their triumph to the heavens. I cheered loudly with the crowd as each crossed their own finish line. When it was finally time to go, I hesitated. It had been a hard struggle, and I was exhausted and ready for sleep, but a part of me didn’t want it to be over. I couldn’t articulate the why in the given moment, but deep down I knew that for a short time I had been a part of something beautiful. I didn’t want to leave that. But everything has its moment, and mine had passed. So I grabbed my buckle and drop bag, and we left.

In the weeks since Sedona Canyons ended, my body has healed and I’ve reveled in what it was able to do. To my immense relief and deep gratitude, my knees held up, and I never fell once. That alone feels like a small miracle. I’ve spent a great deal of time reflecting, trying to ensure each memory is retained. Several of my friends and work colleagues have asked what I thought about during the long hours of the race. I’d expected to have deep thoughts and to ponder life’s mysteries, but honestly I mostly thought nothing at all. As I sank deeper into the pain cave, I became fully tethered to the present—hyper-aware of every sensation. The fire burning through the soles of my feet. The grit of dust collecting in my mouth. The sun pressing against my skin. The steady rhythm of my footsteps against the earth. All of it folded into one continuous, unending moment. A sharp, relentless awareness of being alive.

Now that the race is behind me, there’s a small, quiet emptiness where that dream used to live. A tiny ache, like the one I felt after my daughter was born. I dreamed a beautiful dream, and somehow, it came true. So now the question lingers: what’s next? Cocodona sign-ups have already passed, and this time, I didn’t hit the button. Part of me wanted to, of course—but with our family moving to Seattle and a new assignment aboard ship, next year feels like a swirl of question marks. I’ve been scrolling through Ultrasignup, waiting for something to spark, but so far nothing’s lit that fire. Still, I’m not worried. The flame always comes back. And if it doesn’t? Well, I’ll go chasing it. Because as long as this body still moves, as long as my spirit still stirs, I’ll keep seeking out the edges of myself. The horizon will call again—sooner or later—and when it does, I’ll go.

8 Responses

Erin!!! CONGRATULATIONS on this epic finish and beautiful reflection. We miss you!!

Yay! Hey Sarah! Miss you all too!

I felt every emotion right along with you reading this immersive narrative!! Not only can you run but you can write!

Congratulations on the finish!!

Ps: I need pictures of the potato vest.

Erin, I just read this and it brought tears to my eyes. I am so inspired. Thank you for writing and sharing this! (Lisa from June Boulder retreat)

Wowow congrats, Erin! Love this and what a surprise to see your face pop up on my screen 🙂 We miss you at TS Marin, but so happy to see you crushing it!!

Yay Erin! Beautifully written and congrats on that well-earned buckle! TS Marin misses you! ❤️

As I prepare for my own Sedona 125 journey next May (eeeek), I can’t tell you how much your story moved me. Thank you for such a beautiful account of your experience, Erin and congratulations on such a truly incredible life accomplishment!

Thank you Shannon. Best of luck on your race!!!!